By Anna Pick.

Many AI researchers aim to design machines that replicate or surpass human intelligence. But what counts as ‘intelligence’ is a contentious issue. Dominant strains of computer science, psychology and philosophy have tended to focus on the abstract workings of the mind. But what about the skills that we develop through the body and our interactions with the physical world? Feminists have helped to re-capture the full breadth of abilities and experiences that make us intelligent beings.

***

Artificial intelligence’s diversity problem is well documented. Women are estimated to make up around 12% of machine learning researchers, and earn a smaller share of computing degrees than they did 30 years ago. Only 2.5% of Google’s workforce is black. Feminist writers such as Kate Crawford have also pointed out that those shouting the loudest about the dangers of superintelligence (the so-called ‘Singularitarians’) have tended to be affluent, white and male. So have transhumanists, who believe that humans can, and should, be drastically altered through technological interventions.

Much has been written about the negative impact of a homogenous coding workforce on the quality and bias of algorithms. Less explored is the extent to which this uniformity reinforces conventional understandings of ‘intelligence’. As a recent exhibition at the Barbican in London emphasised, ‘we use AI to understand our own existence’. It is worth reflecting on how AI has been used to make claims about ‘true’ intelligence, and about the kinds of human that are assumed to possess it.

By aiming to imitate or even outstrip human aptitudes for specific tasks, AI research has drawn on deep-rooted assumptions about how humans form knowledge. One important strand can be traced back to the 17th century philosopher Descartes and his distinction between the material body and the immaterial mind. The idea that mind and matter are entirely separate was picked up by Enlightenment philosophers in the 17th and 18th centuries, who associated the mind with pure reason and the natural self. The body, with its passions and desires, was seen, at best, as a ‘container’ of thought, and at worst, as an obstacle to rational thinking.

Early AI researchers aimed to replicate the workings of the brain by turning rational thought into systematic rules. The separation between programme and computer fitted well with Descartes’ conception of the self. The programme, like the mind, was imagined as the producer of knowledge, and the computer, like the body, as a kind of ‘container’ for information or code. Enlightenment framings of the body as a burden, something to be ‘overcome’, was then reproduced by transhumanists, cyberpunk enthusiasts and ‘Singularitarians’, who all expressed their deepest hopes and fears about AI in terms of the triumph of the mind over the body.

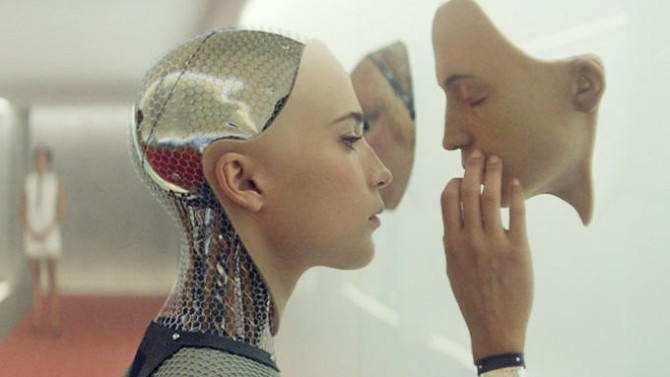

The American futurist Raymond Kurzweil, for instance, argues that the Singularity will also signal the final unification of humans and machines, and popularised the idea of ‘uploading’ a mind to a computer chip, to exist forever in cyberspace. This notion that the mind is ‘computable’ has inspired a wealth of AI-influenced subcultures that promised escape from the body. For instance, the 1980s ‘cyberpunk’ genre of science fiction emphasised the socially transformative potential of new developments in AI and cybernetics. Cyberspace was presented as an escape from corporeal existence, even a chance to make the body obsolete.

Since the beginning, this disdain for the body and the ‘merely mortal’ has been tied up with ideas about gender, race and class. Women’s work has traditionally centred around care of the body and the spaces it occupies. In Enlightenment terms, female labour frees white men in the ruling classes to concentrate on the life of the mind – reason and abstract concepts – which was viewed by many as the highest goal of human existence. Men were thought to have a greater natural capacity for reason and to be less constrained by the body and therefore by emotion, desire, and later, hysteria. At the same time, occupations constructed as ‘feminine’ – usually involving empathy, communication, care – were systematically devalued.

Much AI research, and cyberculture in general, has reinforced the idea that the mind is the producer of knowledge, the body its ‘container’. This is why, for many transhumanists, there is nothing to lose by preserving the mind on a computer chip. Human intelligence is reduced to abstract reasoning power, divorced from any material existence. Again, in computing language, knowledge is represented by ‘zeros’ and ‘ones’ of informational code. This plays into the marginalisation of the body that has historically been used to argue that only affluent white men are truly ‘intelligent’.

By exposing the roots of these ideas and the ways in which they have been instrumentalised in favour of white male dominance, feminists have helped to challenge the idea that human intelligence is ‘disembodied’, or detached from our experience of the physical world. There is a growing school of thought that intelligence of many kinds in fact grows from basic corporeal skills and experiences, including motor control, perception, and, as demonstrated by a fascinating short film produced in Cambridge, emotional responses to pain. Crucially, a number of philosophers and cognitive scientists have shown that reason and emotion are not fundamentally opposed, and many reject the mind-body distinction altogether. For instance, the American academic Martha Nussbaum writes that ‘emotions are not just the fuel that powers the psychological mechanism of a reasoning creature, they are parts, highly complex and messy parts, of this creature’s reasoning itself.’

Alternative branches of AI have supported the idea that intelligence is intimately connected to the body. From the 1960s, cybernetics aimed at studying ‘life’ rather than ‘mind’, and seemed to suggest the importance of the body in informing cognition and behaviour. More recently, A-Life (Artificial Life) researchers have begun to study ‘natural’ life and create ‘life like’ behaviour through robotics.

The insight that we acquire key skills by learning ‘through the body’ is essential for designers of AI machines. What it means for transhumanists is unclear. The recent HBO series Years and Years has renewed popular interest in the idea that we could ‘upload’ the conscious mind and shed the body (which the character Edith Lyons does through a dystopian Amazon Alexa-style device by the year 2034). This kind of preservation only makes sense if you believe (in my view, mistakenly) that the body is marginal, not only to intelligence, but also to our sense of ‘self’. The question for transhumanists is whether the virtual could ever replicate the physical convincingly enough to capture the full breadth of the human experience.

Anna Pick is Research, Advocacy and Communications Coordinator at Future Advocacy.