BLOG

Digital Technology: When, Why and How is it being used (or not used) in England and Wales’ test and trace efforts

By Rashidat Animashaun

States that have maximised digital technology and integrated it into their track and trace efforts have been most effective at curbing the spread of Covid-19. So how have England and Wales (Scotland and Northern Ireland have separate track and trace systems) integrated – or not integrated- digital technology into its track and trace efforts, and could this be one reason why we have the number of cases and deaths that we do?

Many East and Southeast Asian states, praised for their effective response to the pandemic, have engaged and deployed digital technology to trace and control the spread of Covid-19. In Wuhan, AI was used in large crowds to identify those with high temperatures. Half a year before the launch of our NHS track and trace app, Singapore had a mobile app called TraceTogether that enabled community-driven contact tracing in much the same way as our current NHS track and trace app works. TraceTogether uses Bluetooth signal whenever its user’s app detects another phone with the app installed.

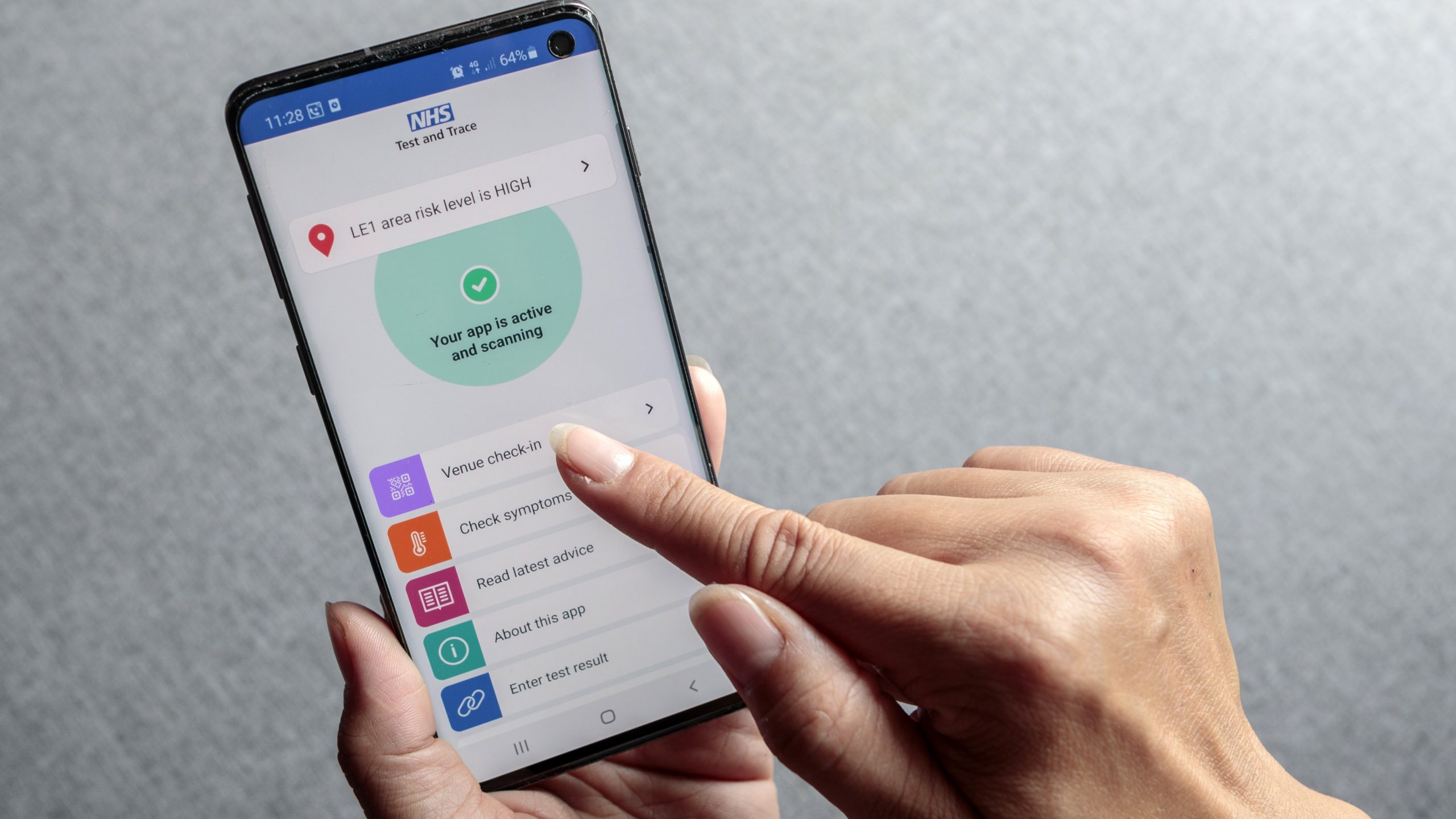

In England and Wales, our integration of digital technology focuses on the contact-tracing app. The app was meant to be integral to our track and trace efforts, but the app’s delay has meant it is more of an addition to track and trace.

Test and trace

During the creation of our contact tracing app, there was debate over a centralised or decentralised approach. In a centralised approach, data is first sent to a central server before sent to individuals. In a decentralised system notifications are sent to individuals directly, without a central server. NHSX sought a centralised approach over the more decentralised approach of Apple and Google, arguing that a centralised approach provided more useful information. After just 2 months of trying a centralised approach, NHSX in collaboration with Apple and Google pursued a decentralised approach.

In part, a preference for a centralised system may come from a desire to use AI to its full capacity. Machine learning, a driver of AI, requires large amounts of data to detect patterns and predict future outcomes. A centralised system would provide this large amount of data for AI use, explaining NHSX’s preference for it.

A debate over centralisation versus a localised approach also plagues the non-digital aspects of the NHS Track and Trace System. The NHS collects the initial contact information and Serco gets in touch with contacts of the positive patient. Some are adamant that a localised system of test and trace works more effectively than the centralised operation pursued by the government.

Sometimes those who test positive are cagey about sharing details of their recent contacts. Our app, in its current form, cannot overcome this; the NHS app isn’t mandatory, and even when downloaded, its contact tracing feature can be switched off. While location-tracking digitised systems could overcome these obstacles (discussed further below), current concerns around privacy and state surveillance make this unlikely. It is also worth considering how a phone conversation could draw people out of their cagey-ness and convince them that they are not at risk of punitive reactions by the state. There is only so much our current use of digital technology can do – it is far from a silver bullet to solve all shortfalls in our current Test and Trace efforts.

Enforcement

Another key issue in England and Wales’ track and trace efforts is that many people who have come into “high risk” contact with the disease fail to self-isolate. Studies have also found that young people and those on low incomes who cannot work from home were most likely to break the rules of self-isolation.

South Korea has used GPS phone tracking, credit card history surveillance video recording and daily calls to those at risk of infection and those who have been asked to quarantine to ensure compliance. In Hong Kong new arrivals were made to download the StayHomeSafe app and given a wristband to help catch violators of the mandatory 14 day quarantine upon arrival. But such measures could be seen in England and Wales as a violation of civil liberties, with a second lockdown beginning earlier this month, branded by some as “authoritarian” in nature.

Fear of a “Big Brother” state engaged in geo-tracing or nefarious use of data has plagued government-initiated AI projects before. So concerned were some about the potential implications of a mobile contact tracing app to deal with this pandemic that a draft basic safeguards bill was written. The government has gone on record to say that the app uses a minimal amount of data and the data that is used is anonymised. Indeed the initial app which cost £10 million was later abandoned in part due to concerns around data protection and privacy.

A public embrace?

Arguments around the success of many East and Southeast Asian states centre on their “collectivist spirits” and supposed limited regard for civil liberties as their basis for success. More useful to this discussion would be to focus on how frequently our part of the world has dealt with a serious outbreak in this current digital age. Some discussions of the great East Asian response have referenced the impact of MERS outbreaks in 2015 and before that, the SARS outbreak. The result of these outbreaks means greater experience with how to use technology in an infectious disease outbreak. Rather than Britain being a less collectivist country and one more distrusting of technology, there is greater unfamiliarity and experience with infectious disease outbreaks and the positives of the integration of digital initiatives to our disease-tracing efforts.

Better use of machine learning requires time for AI to get acquainted with this type of new data before it can effectively identify trends and patterns. This will likely not be our last pandemic and thus the lessons learnt and technology used can better prepare us for future outbreaks.

What more does digital technology have to offer?

Quite recently, the government has also decided to use AI and machine learning to analyse existing Test and Trace data. This statistical modelling and machine learning will provide independent analysis of NHS Test and Trace data to give predictions on what the virus might do next.

When, Why, and How has digital technology been used in track and trace?

We can conclude, digital technology’s use in track and trace is still in its infancy, and rightly so. Aspects of our track and trace systems still need a good degree of human interaction. Where technology is being used, it ought to be explained, understood, and consented to. Only then can we build the trust and familiarity needed for its deployment in future disease outbreaks.